|

Topics

Introduction

Problems Freedom Knowledge Mind Life Chance Quantum Entanglement Scandals Philosophers Mortimer Adler Rogers Albritton Alexander of Aphrodisias Samuel Alexander William Alston Anaximander G.E.M.Anscombe Anselm Louise Antony Thomas Aquinas Aristotle David Armstrong Harald Atmanspacher Robert Audi Augustine J.L.Austin A.J.Ayer Alexander Bain Mark Balaguer Jeffrey Barrett William Barrett William Belsham Henri Bergson George Berkeley Isaiah Berlin Richard J. Bernstein Bernard Berofsky Robert Bishop Max Black Susan Blackmore Susanne Bobzien Emil du Bois-Reymond Hilary Bok Laurence BonJour George Boole Émile Boutroux Daniel Boyd F.H.Bradley C.D.Broad Michael Burke Jeremy Butterfield Lawrence Cahoone C.A.Campbell Joseph Keim Campbell Rudolf Carnap Carneades Nancy Cartwright Gregg Caruso Ernst Cassirer David Chalmers Roderick Chisholm Chrysippus Cicero Tom Clark Randolph Clarke Samuel Clarke Anthony Collins August Compte Antonella Corradini Diodorus Cronus Jonathan Dancy Donald Davidson Mario De Caro Democritus William Dembski Brendan Dempsey Daniel Dennett Jacques Derrida René Descartes Richard Double Fred Dretske Curt Ducasse John Earman Laura Waddell Ekstrom Epictetus Epicurus Austin Farrer Herbert Feigl Arthur Fine John Martin Fischer Frederic Fitch Owen Flanagan Luciano Floridi Philippa Foot Alfred Fouilleé Harry Frankfurt Richard L. Franklin Bas van Fraassen Michael Frede Gottlob Frege Peter Geach Edmund Gettier Carl Ginet Alvin Goldman Gorgias Nicholas St. John Green Niels Henrik Gregersen H.Paul Grice Ian Hacking Ishtiyaque Haji Stuart Hampshire W.F.R.Hardie Sam Harris William Hasker R.M.Hare Georg W.F. Hegel Martin Heidegger Heraclitus R.E.Hobart Thomas Hobbes David Hodgson Shadsworth Hodgson Baron d'Holbach Ted Honderich Pamela Huby David Hume Ferenc Huoranszki Frank Jackson William James Lord Kames Robert Kane Immanuel Kant Tomis Kapitan Walter Kaufmann Jaegwon Kim William King Hilary Kornblith Christine Korsgaard Saul Kripke Thomas Kuhn Andrea Lavazza James Ladyman Christoph Lehner Keith Lehrer Gottfried Leibniz Jules Lequyer Leucippus Michael Levin Joseph Levine George Henry Lewes C.I.Lewis David Lewis Peter Lipton C. Lloyd Morgan John Locke Michael Lockwood Arthur O. Lovejoy E. Jonathan Lowe John R. Lucas Lucretius Alasdair MacIntyre Ruth Barcan Marcus Tim Maudlin James Martineau Nicholas Maxwell Storrs McCall Hugh McCann Colin McGinn Michael McKenna Brian McLaughlin John McTaggart Paul E. Meehl Uwe Meixner Alfred Mele Trenton Merricks John Stuart Mill Dickinson Miller G.E.Moore Ernest Nagel Thomas Nagel Otto Neurath Friedrich Nietzsche John Norton P.H.Nowell-Smith Robert Nozick William of Ockham Timothy O'Connor Parmenides David F. Pears Charles Sanders Peirce Derk Pereboom Steven Pinker U.T.Place Plato Karl Popper Porphyry Huw Price H.A.Prichard Protagoras Hilary Putnam Willard van Orman Quine Frank Ramsey Ayn Rand Michael Rea Thomas Reid Charles Renouvier Nicholas Rescher C.W.Rietdijk Richard Rorty Josiah Royce Bertrand Russell Paul Russell Gilbert Ryle Jean-Paul Sartre Kenneth Sayre T.M.Scanlon Moritz Schlick John Duns Scotus Albert Schweitzer Arthur Schopenhauer John Searle Wilfrid Sellars David Shiang Alan Sidelle Ted Sider Henry Sidgwick Walter Sinnott-Armstrong Peter Slezak J.J.C.Smart Saul Smilansky Michael Smith Baruch Spinoza L. Susan Stebbing Isabelle Stengers George F. Stout Galen Strawson Peter Strawson Eleonore Stump Francisco Suárez Richard Taylor Kevin Timpe Mark Twain Peter Unger Peter van Inwagen Manuel Vargas John Venn Kadri Vihvelin Voltaire G.H. von Wright David Foster Wallace R. Jay Wallace W.G.Ward Ted Warfield Roy Weatherford C.F. von Weizsäcker William Whewell Alfred North Whitehead David Widerker David Wiggins Bernard Williams Timothy Williamson Ludwig Wittgenstein Susan Wolf Xenophon Scientists David Albert Philip W. Anderson Michael Arbib Bobby Azarian Walter Baade Bernard Baars Jeffrey Bada Leslie Ballentine Marcello Barbieri Jacob Barandes Julian Barbour Horace Barlow Gregory Bateson Jakob Bekenstein John S. Bell Mara Beller Charles Bennett Ludwig von Bertalanffy Susan Blackmore Margaret Boden David Bohm Niels Bohr Ludwig Boltzmann John Tyler Bonner Emile Borel Max Born Satyendra Nath Bose Walther Bothe Jean Bricmont Hans Briegel Leon Brillouin Daniel Brooks Stephen Brush Henry Thomas Buckle S. H. Burbury Melvin Calvin William Calvin Donald Campbell John O. Campbell Sadi Carnot Sean B. Carroll Anthony Cashmore Eric Chaisson Gregory Chaitin Jean-Pierre Changeux Rudolf Clausius Arthur Holly Compton John Conway Simon Conway-Morris Peter Corning George Cowan Jerry Coyne John Cramer Francis Crick E. P. Culverwell Antonio Damasio Olivier Darrigol Charles Darwin Paul Davies Richard Dawkins Terrence Deacon Lüder Deecke Richard Dedekind Louis de Broglie Stanislas Dehaene Max Delbrück Abraham de Moivre David Depew Bernard d'Espagnat Paul Dirac Theodosius Dobzhansky Hans Driesch John Dupré John Eccles Arthur Stanley Eddington Gerald Edelman Paul Ehrenfest Manfred Eigen Albert Einstein George F. R. Ellis Walter Elsasser Hugh Everett, III Franz Exner Richard Feynman R. A. Fisher David Foster Joseph Fourier George Fox Philipp Frank Steven Frautschi Edward Fredkin Augustin-Jean Fresnel Karl Friston Benjamin Gal-Or Howard Gardner Lila Gatlin Michael Gazzaniga Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen GianCarlo Ghirardi J. Willard Gibbs James J. Gibson Nicolas Gisin Paul Glimcher Thomas Gold A. O. Gomes Brian Goodwin Julian Gough Joshua Greene Dirk ter Haar Jacques Hadamard Mark Hadley Ernst Haeckel Patrick Haggard J. B. S. Haldane Stuart Hameroff Augustin Hamon Sam Harris Ralph Hartley Hyman Hartman Jeff Hawkins John-Dylan Haynes Donald Hebb Martin Heisenberg Werner Heisenberg Hermann von Helmholtz Grete Hermann John Herschel Francis Heylighen Basil Hiley Art Hobson Jesper Hoffmeyer John Holland Don Howard John H. Jackson Ray Jackendoff Roman Jakobson E. T. Jaynes William Stanley Jevons Pascual Jordan Eric Kandel Ruth E. Kastner Stuart Kauffman Martin J. Klein William R. Klemm Christof Koch Simon Kochen Hans Kornhuber Stephen Kosslyn Daniel Koshland Ladislav Kovàč Leopold Kronecker Bernd-Olaf Küppers Rolf Landauer Alfred Landé Pierre-Simon Laplace Karl Lashley David Layzer Joseph LeDoux Gerald Lettvin Michael Levin Gilbert Lewis Benjamin Libet David Lindley Seth Lloyd Werner Loewenstein Hendrik Lorentz Josef Loschmidt Alfred Lotka Ernst Mach Donald MacKay Henry Margenau Lynn Margulis Owen Maroney David Marr Humberto Maturana James Clerk Maxwell John Maynard Smith Ernst Mayr John McCarthy Barbara McClintock Warren McCulloch N. David Mermin George Miller Stanley Miller Ulrich Mohrhoff Jacques Monod Vernon Mountcastle Gerd B. Müller Emmy Noether Denis Noble Donald Norman Travis Norsen Howard T. Odum Alexander Oparin Abraham Pais Howard Pattee Wolfgang Pauli Massimo Pauri Wilder Penfield Roger Penrose Massimo Pigliucci Steven Pinker Colin Pittendrigh Walter Pitts Max Planck Susan Pockett Henri Poincaré Michael Polanyi Daniel Pollen Ilya Prigogine Hans Primas Giulio Prisco Zenon Pylyshyn Henry Quastler Adolphe Quételet Pasco Rakic Nicolas Rashevsky Lord Rayleigh Frederick Reif Jürgen Renn Giacomo Rizzolati A.A. Roback Emil Roduner Juan Roederer Robert Rosen Frank Rosenblatt Jerome Rothstein David Ruelle David Rumelhart Michael Ruse Stanley Salthe Robert Sapolsky Tilman Sauer Ferdinand de Saussure Jürgen Schmidhuber Erwin Schrödinger Aaron Schurger Sebastian Seung Thomas Sebeok Franco Selleri Claude Shannon James A. Shapiro Charles Sherrington Abner Shimony Herbert Simon Dean Keith Simonton Edmund Sinnott B. F. Skinner Lee Smolin Ray Solomonoff Herbert Spencer Roger Sperry John Stachel Kenneth Stanley Henry Stapp Ian Stewart Tom Stonier Antoine Suarez Leonard Susskind Leo Szilard Max Tegmark Teilhard de Chardin Libb Thims William Thomson (Kelvin) Richard Tolman Giulio Tononi Peter Tse Alan Turing Robert Ulanowicz C. S. Unnikrishnan Nico van Kampen Francisco Varela Vlatko Vedral Vladimir Vernadsky Clément Vidal Mikhail Volkenstein Heinz von Foerster Richard von Mises John von Neumann Jakob von Uexküll C. H. Waddington Sara Imari Walker James D. Watson John B. Watson Daniel Wegner Steven Weinberg August Weismann Paul A. Weiss Herman Weyl John Wheeler Jeffrey Wicken Wilhelm Wien Norbert Wiener Eugene Wigner E. O. Wiley E. O. Wilson Günther Witzany Carl Woese Stephen Wolfram H. Dieter Zeh Semir Zeki Ernst Zermelo Wojciech Zurek Konrad Zuse Fritz Zwicky Presentations ABCD Harvard (ppt) Biosemiotics Free Will Mental Causation James Symposium CCS25 Talk Evo Devo September 12 Evo Devo October 2 Evo Devo Goodness Evo Devo Davies Nov12 |

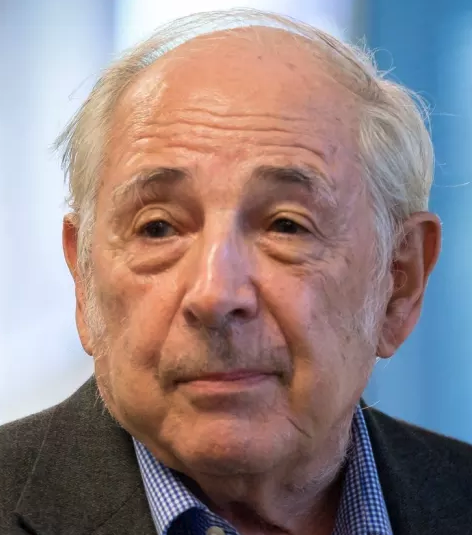

John Searle

the basic idea is clear enough. In our dealings with nature we assume that everything that happens occurs as a result of antecedently sufficient causal conditions. And when we give an explanation by citing a cause, we assume that the cause we cite, together with the rest of the context, was sufficient to bring about the event we are explaining.(p.44)In his 2010 essay, Consciousness and the Problem of Free Will, Searle makes clear that the "problem of free will" arises in the context of his simplistic notion of the natural world. The problem of free will arises because there is a conflict between two deeply held convictions and we do not see how to shake off either conviction. The first conviction is that human actions are natural events like any other events in the world. Human actions are part of the natural world as much as human digestion and human growth, along with the movement of tectonic plates and the growth of seeds into plants, and as such they are subject to natural forces. But this seems to imply that human actions are entirely determined, that they are as determined as any other biological process or, for that matter, any natural process in the world. (Free Will and Consciousness,, Baumeister et al., p.124)Searle is completely wrong about nature. Creative cosmic processes have always had a free element followed by an adequately determined selection process, such as biological evolution. But, Searle says, we cannot proceed without assuming freedom - it is presupposed, an axiom. The scientific problem of free will is not a problem in language or logic, depending on definitions and axioms. Searle is interested in the "traditional" philosophical problem of free will. : The problem of free will is unusual among contemporary philosophical issues in that we are nowhere remotely near to having a solution. I can give you a pretty good account of consciousness, intentionality, speech acts and of the ontology of society but I do not know how to solve the problem of free will. Well, why is that important? There are lots of problems we do not have solutions to. The special problem of free will is that we cannot get on with our lives without presupposing free will. Whenever we are in a decision-making situation, or indeed, in any situation that calls for voluntary action, we have to presuppose our own freedom. (Freedom and Neurobiology, p.11)In 2007 and a breakthrough of sorts, Searle admits that he could never see, until now, the point of introducing quantum mechanics into discussions of consciousness and free will. Now he says we know two things: First we know that our experiences of free action contain both indeterminism and rationality...Second we know that quantum indeterminacy is the only form of indeterminism that is indisputably established as a fact of nature...it follows that quantum mechanics must enter into the explanation of consciousness." (F&N, p.74-75)He describes the discovery of irreducible quantum randomness in the universe. An interesting change occurred in the early decades of the twentieth century. At the most fundamental level of physics, nature turns out not to be in that way deterministic. We have come to accept at a quantum mechanical level explanations that are not deterministic. However, so far quantum indeterminism gives us no help with the free will problem, because that indeterminism introduces randomness into the basic structure of the universe, and the hypothesis that some of our acts occur freely is not at all the same as the hypothesis that some of our acts occur at random. I will have more to say about this issue later. (F&N,p.44) There are a number of accounts that seem to explain consciousness and even free will in terms of quantum mechanics. I have never seen anything that was remotely convincing, but it is important for this discussion that we remember that as far as our actual theories of the universe are concerned, at the most fundamental level we have come to think that it is possible to have explanations of natural phenomena that are not deterministic. And that possibility will be important when we later discuss the problem of free will as a neurobiological problem. (F&N,p.45)We have identified several mechanisms for free will involving quantum mechanics. Searle is quite right that most of them are not convincing. Searle argues for a fundamental difference between passive activities like perceptions and the active character of what he calls "volitional consciousness." For example, if I am standing in a park looking at a tree, there is a sense in which it is not up to me what I experience. It is up to how the world is and how my perceptual apparatus is. But if I decide to walk away or raise my arm or scratch my head, then I find a feature of my experiences of free, voluntary actions that was not present in my perceptions. The feature is that I do not sense the antecedent causes of my action in the form of reasons, such as beliefs and desires, as setting causally sufficient conditions for the action; and, which is another way of saying the same thing, I sense alternative courses of action open to me. (p.41)Searle senses a "gap" between the decision and the action. In typical cases of deliberating and acting, there is, in short, a gap, or a series of gaps, between the causes of each stage in the processes of deliberating, deciding and acting, and the subsequent stages. If we probe more deeply we can see that the gap can be divided into different sorts of segments. There is a gap between the reasons for the decision and the making of the decision. There is a gap between the decision and the onset of the action. (F&N, p.42)For Searle, his "gap" is the possible home of the mysterious causa sui that makes us "feel" our volitions are up to us and not just happening to us like our perceptions and other external events. But our freedom from deterministic causes is much deeper than our subjective feelings, being "conscious" of our decisions and actions. Many of our decisions and actions are "sub-conscious" and automatic. We would be hopelessly slowed down if every act had to rise to the level of a conscious deliberation and subjective feelings. Searle describes "open" alternative courses of action. It is very important to place the "gap" or causa sui before or during the generation of these alternative possibilities for deliberation to be followed by willed action. The result is a two-stage, temporal-sequence model with no need for Searle's later causal gaps. He said three things are necessary:

For Teachers

For Scholars

Excerpts from Freedom and Neurobiology

From Philosophy and the Basic Facts (p.11)

The problem of free will is unusual among contemporary philosophical issues in that we are nowhere remotely near to having, a solution. I can give you a pretty good account of consciousness, intentionality, speech acts and of the ontology of society but I do not know how to solve the problem of free will.

Well, why is that important? There are lots of problems we do not have solutions to. The special problem of free will is that we cannot get on with our lives without presupposing free will. Whenever we are in a decision-making situation, or indeed, in any situation that calls for voluntary action, we have to presuppose our own freedom. Suppose you are given a choice in a restaurant between steak and veal. The waiter asks you "And sir, which would you prefer, the steak or the veal?" You cannot say to the waiter,"Look, I am a determinist. I will just wait and see what I order because I know,that my order is determined.' The refusal, i.e. the conscious, intentional speech act of refusing to place an order, is only intelligible to you if you understand it as an exercise of your own free will. The point that I am making now is not that free will is a fact. We don't know if it is a fact. The point is that given the structure of our consciousness, we cannot proceed except on the position of free will.

From Free Will as a Problem in Neurobiology (pp.37-47)

The persistence of the traditional free will problem in philosophy seems to me something of a scandal. After all these centuries of writing about free will, it does not seem to me that we have made very much progress.

Is there some conceptual problem that we are unable to overcome? Is there some fact that we have simply ignored? Why is it that we have made so little advance over our philosophical ancestors?

Typically, when we encounter one of these problems that seems insoluble it has a certain logical form. On the one hand we have a belief or a set of beliefs that we feel we really cannot give up, but on the other hand, we have another belief or set of beliefs that is inconsistent with the first set, and seems just as compelling as the first set. So, for example, in the old mind-body problem we have the belief that the world consists entirely of material particles in fields of force, but at the same time the world seems to contain consciousness, an immaterial phenomenon; and we cannot see how to put the immaterial together with the material into a coherent picture of the universe. In the old problem of skeptical epistemology, it seems, on the one hand, according to common sense, that we do have certain knowledge of many things in the world, and yet, on the other hand, if we really have such knowledge, we ought to be able to give a decisive answer to the skeptical arguments, such as, How do we know we are not dreaming, are not a brain in a vat, are not being deceived by evil demons, etc.? But we do not know how to give a conclusive answer to these skeptical challenges. In the case of free will the problem is that we think explanations of natural phenomena should be completely deterministic. The explanation of the Loma Prieta earthquake, for example, does not explain why it just happened to occur, it explains why it had to occur. Given the forces operating on the tectonic plates, there was no other possibility. But at the same time, when it comes to explaining a certain class of human behavior, it seems that we typically have the experience of acting "freely" or "voluntarily" in a sense of these words that makes it impossible to have deterministic explanations. For example, it seems that when I voted for a particular candidate and did so for a certain reason, well, all the same, I could have voted for the other candidate all other conditions remaining the same. Given the causes operating on me, I did not have to vote for that candidate. So when I cite the reason as an explanation of my action I am not citing causally sufficient conditions. So we seem to have a contradiction. On the one hand we have the experience of freedom, and on the other hand we find it very hard to give up the view that because every event has a cause, and human actions are events, they must have sufficient causal explanations as much as earthquakes or rain storms.

When we at last overcome one of these intractable problems it often happens that we do so by showing that we had made a false presupposition. In the case of the mind-body problem, we had, I believe, a false presupposition in the very terminology, in which we stated the problem. The terminology of mental and physical, of materialism and dualism, of spirit and flesh, contains a false presupposition that these must name mutually exclusive categories of reality — that our conscious states qua subjective, private, qualitative, etc. cannot be ordinary physical, biological features of our brain. Once we overcome that presupposition, the presupposition that the mental and the physical naively construed are mutually exclusive, then it seems to me we have a solution to the traditional mind-body problem. And here it is: All of our mental states are caused by neurobiological processes in the brain, and they are themselves realized in the brain as its higher-level or system features. So, for example, if you have a pain, your pain is caused by sequences of neuron firings, and the actual realization of the pain experience is in the brain.

The solution to the philosophical mind-body problem seems to me not very difficult. However, the philosophical solution kicks the problem upstairs to neurobiology, where it leaves us with a very difficult neurobiological problem. How exactly does the brain do it, and how exactly are conscious states realized in the brain? What exactly are the neuronal processes that cause our conscious experiences, and how exactly are these conscious experiences realized in brain structures?

Perhaps we can make a similar transformation of the problem of free will. Perhaps if we analyze the problem sufficiently, and remove various philosophical confusions, we can see that the remaining problem is essentially a problem about how the brain works. In order to work toward that objective I need first to clarify a number of philosophical issues.

Let us begin by asking why we find the conviction of our own free will so difficult to abandon. I believe that this conviction arises from some pervasive features of conscious experience. If you consider ordinary conscious activities such as ordering a beer in a pub, watching a movie, or trying to do your income tax, you discover that there is a striking difference between the passive character of perceptual consciousness and the active character of what we might call "volitional consciousness" For example, if I am standing in a park looking at a tree, there is a sense in which it is not up to me what I experience. It is up to how the world is and how my perceptual apparatus is. But if I decide to walk away or raise my arm or scratch my head, then I find a feature of my experiences of free, voluntary actions that was not present in my perceptions. The feature is that I do not sense the antecedent causes of my action in the form of reasons, such as beliefs and desires, as setting causally sufficient conditions for the action; and, which is another way of saying the same thing, I sense alternative courses of action open to me.

You see this strikingly if you consider cases of rational decision making. I recently had to decide which candidate to vote for in a presidential election. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that I voted for George W. Bush. I had certain reasons for voting for Bush, and certain other reasons for not voting for Bush. But, interestingly, when I chose to vote for Bush on the basis of some of those reasons and not others, and later when I actually cast a vote for Bush in a voting booth, I did not sense the antecedent causes of my action as setting causally sufficient conditions. I did not sense the reasons for making the decision as causally sufficient to force the decision, and I did not sense the decision itself as causally sufficient to force the action. In typical cases of deliberating and acting, there is, in short, a gap, or a series of gaps, between the causes of each stage in the processes of deliberating, deciding and acting, and the subsequent stages. If we probe more deeply we can see that the gap can be divided into different sorts of segments. There is a gap between the reasons for the decision and the making of the decision. There is a gap between the decision and the onset of the action, and for any extended action, such as when I am trying to learn German or to swim the English Channel, there is a gap between the onset of the action and its continuation to completion. In this respect, voluntary actions are quite different from per- ceptions. There is indeed a voluntaristic element in perception. I can, for example, choose to see the ambiguous figure either as a duck or a rabbit, but for the most part my perceptual experiences are causally fixed. That is why we have a problem of the freedom of the will, but

we do not have a problem of the freedom of perception. The gap, as I have described it, is a feature of our conscious, voluntary activities. At each stage, the conscious states are not experienced as sufficient to compel the next conscious state. There is thus only one continuous experience of the gap, but we can divide it into three different sorts of manifestations, as I did above. The gap is between one conscious state and the next, not between conscious states and bodily movements or between physical stimuli and conscious states.

This experience of free will is very compelling, and even those of us who think it is an illusion find that we cannot in practice act on the presupposition that it is an illusion. On the contrary, we have to act on the presupposition of freedom. Imagine that you are in a restaurant and you are given a choice between veal and pork, and you have to make up your mind. You cannot refuse to exercise free will in such a case, because the refusal itself is only intelligible to you as a refusal if you take it as an exercise of free will. So if you say to the waiter, "Look, I am a determinist — che sara sara, I'll just wait and see what I order," that refusal to exercise free will is only intelligible to you as one of your actions if you take it to be an exercise of your free will. Kant pointed this out a long time ago. We cannot think away our free will. The conscious experiences of the gap give us the conviction of human freedom.

If we now turn to the opposing view and ask why we are so convinced of determinism, the arguments for determinism seem just as compelling as the arguments for free will. A basic feature of our relation to the world is that we find the world causally ordered. Natural phenomena in the world have causal explanations, and those causal explanations state causally sufficient conditions. Customarily, in philosophy, we put this point by saying that that every event has a cause, That formulation is, of course, much too crude to capture the complexity of the idea of causation that we are working with. But the basic idea is clear enough. In our dealings with nature we assume that everything that happens occurs as a result of antecedently sufficient causal conditions. And when we give an explanation by citing a cause, we assume that the cause we cite, together with the rest of the context, was sufficient to bring about the event we are explaining. In my earlier example of the earthquake, we assume that the event did not just happen to occur, in that situation it had to occur. In that context the causes were sufficient to determine the event.

An interesting change occurred in the early decades of the twentieth century. At the most fundamental level of physics, nature turns out not to be in that way deterministic. We have come to accept at a quantum mechanical level explanations that are not deterministic. However, so far quantum indeterminism gives us no help with the free will problem, because that indeterminism introduces randomness into the basic structure of the universe, and the hypothesis that some of our acts occur freely is not at all the same as the hypothesis that some of our acts occur at random. I will have more to say about this issue later.

There are a number of accounts that seem to explain consciousness and even free will in terms of quantum mechanics. I have never seen anything that was remotely convincing, but it is important for this discussion that we remember that as far as our actual theories of the universe are concerned, at the most fundamental level we have come to think that it is possible to have explanations of natural phenomena that are not deterministic. And that possibility will be important when we later discuss the problem of free will as a neurobiological problem.

It is important to emphasize that the problem of free will, as I have stated it, is a problem about a certain kind of human consciousness. Without the conscious experience of the gap, that is, without the conscious experience of the distinctive features of free, voluntary, rational actions, there would be no problem of free will. We have the conviction of our own free will because of certain features of our consciousness. The question is: Granted that we have the experience of freedom, is that experience valid or is it illusory? Does that experience correspond to something in reality beyond the experience itself? We have to assume that there are causal antecedents to our actions. The question is: Are those causal antecedents in case sufficient to determine the action, or are there some cases where they are not sufficient, and, if so, how do we account for those cases?

Let us take stock of where we are. On the one hand we have the experience of freedom, which, as I have described it, is the experience of the gap. The gap between the antecedent causes of our free, voluntary decisions and actions and the actual making of those decisions and the performance of those actions. On the other hand we have the presupposition, or the assumption, that nature is a matter of events occurring according to causally sufficient conditions, and we find it difficult to suppose that we could explain any phenomena without appealing to causally sufficient conditions.

For the purposes of the discussion that follows, I am going to assume that the experiences of the gap are psychologically valid. That is, I am going to assume that for many voluntary, free, rational human actions, the purely psychological antecedents of the action are not causally sufficient to determine the action. This occurred, for example, when I selected a candidate to vote for in the last American presidential election. I realize that a lot of people think that psychological determinism is true, and I have certainly not given a decisive refutation of it. Nonetheless, it seems to me we find the psychological experience of freedom so compelling that it would be absolutely astounding if it turned out that at the psychological level it was a massive illusion, that all of our behavior was psychologically compulsive. There are arguments against psychological determinism, but I am not going to present them in this chapter. I am going to assume that psychological determinism is false, and that the real problem of determinism is not at the psychological level, but at a more fundamental neurobiological level.

Furthermore, there are several famous issues about free will that I will not discuss, and I mention them here only to set them aside. I will have nothing to say about compatibilism, the view that free will and determinism are really consistent with each other. According to the definitions of these terms that I am using, determinism and free will are not compatible. The thesis of determinism asserts that all actions are preceded by sufficient causal conditions that determine them. The thesis of free will asserts that some actions are not preceded by sufficient causal conditions. Free will so defined is the negation of determinism. No doubt there is a sense of these words where free will is compatible with determinism (when, for example, people march in the streets carrying signs that say, "Freedom Now," they are presumably not interested in physical or neurobiological laws), but that is not the sense of these terms that concerns me. I will also have nothing to say about moral responsibility. Perhaps there is some interesting connection between the problem of free will and the problem of moral responsibility, but if so I will have nothing to say about it in this chapter.

Excerpts from Mind, Brains, and Science, 1984

Chapter 4 The Freedom of the Will (pp.86-99)

In these pages, I have tried to answer what to me are some of the most worrisome questions about how we as human beings fit into the rest of the universe. Our conception of ourselves as free agents is fundamental to our overall self-conception. Now, ideally, I would like to be able to keep both my commonsense conceptions and my scientific beliefs. In the case of the relation between mind and body, for example, I was able to do that. But when it comes to the question of freedom and determinism, I am – like a lot of other philosophers – unable to reconcile the two.

One would think that after over 2000 years of worrying about it, the problem of the freedom of the will would by now have been finally solved. Well, actually most philosophers think it has been solved. They think it was solved by Thomas Hobbes and David Hume and various other empirically-minded philosophers whose solutions have been repeated and improved right into the twentieth century. I think it has not been solved. In this lecture I want to give you an account of what the problem is, and why the contemporary solution is not a solution, and then conclude by trying to explain why the problem is likely to stay with us.

On the one hand we are inclined to say that since nature consists of particles and their relations with each other, and since everything can be accounted for in terms of those particles and their relations, there is simply no room for freedom of the will. As far as human freedom is concerned, it doesn't matter whether physics is deterministic, as Newtonian physics was, or whether it allows for an indeterminacy at the level of particle support at all to any doctrine of the freedom of the will; because first, the statistical indeterminacy at the level of particles does not show any indeterminacy at the level of the objects that matter to us – human bodies, for example. And secondly, even if there is an element of indeterminacy in the behaviour of physical particles – even if they are only statistically predictable – still, that by itself gives no scope for human freedom of the will; because it doesn't follow from the fact that particles are only statistically determined that the human mind can force the statistically-determined particles to swerve from their paths. Indeterminism is no evidence that there is or could be some mental energy of human freedom that can move molecules in directions that they were not otherwise going to move. So it really does look as if everything we know about physics forces us to some form of denial of human freedom.

The strongest image for conveying this conception of determinism is still that formulated by Laplace: If an ideal observer knew the positions of all the particles at a given instant and knew all the laws governing their movements, he could predict and retrodict the entire history of the universe. Some of the predictions of a contemporary quantum-mechanical Laplace might be statistical, but they would still allow no room for freedom of the will.

So much for the appeal of determinism. Now let's turn to the argument for the freedom of the will. As many philosophers have pointed out, if there is any fact of experience that we are all familiar with, it's the simple fact that our own choices, decisions, reasonings, and cogitations seem to make a difference to our actual behaviour. There are all sorts of experiences that we have in life where it seems just a fact of our experience that though we did one thing, we feel we know perfectly well that we could have done something else. We know we could have done something else, because we chose one thing for certain reasons. But we were aware that there were also reasons for on those reasons and chosen that something else. Another way to put this point is to say : it is just a plain empirical fact about our behaviour that it isn't predictable in the way that the behaviour of objects rolling down an inclined plane is predictable. And the reason it isn't predictable in that way is that we could often have done otherwise than we in fact did. Human freedom is just a fact of experience. If we want some empirical proof of this fact, we can simply point to the further fact that it is always up to us to falsify any predictions anybody might care to make about our behaviour. If somebody predicts that I am going to do something, I might just damn well do something else. Now, that sort of option is simply not open to glaciers moving down mountainsides or balls rolling down inclined planes or the planets moving in their elliptical orbits.

This is a characteristic philosophical conundrum. On the one hand, a set of very powerful arguments force us to the conclusion that free will has no place in the universe. On the other hand, a series of powerful arguments based on facts of our own experience inclines us to the conclusion that there must be some freedom of the will because we all experience it all the time.

There is a standard solution to this philosophical conundrum. According to this solution, free will and determinism are perfectly compatible with each other. Of course, everything in the world is determined, but some human actions are nonetheless free. To say that they are free is not to deny that they are determined; it is just to say that they are not constrained. We are not forced to do them, So, for example, if a man is forced to do something at gunpoint, or if he is suffering from some psychological compulsion, then his behaviour is genuinely unfree. But if on the other hand he freely acts, if he acts, as we say, of his own free will, then his behaviour is free. Of course it is also completely determined, since every aspect of his behaviour is determined by the physical forces operating on the particles that compose his body, as they operate on all of the bodies in the universe. So, free behaviour exists, but it is just a small corner of the determined world – it is that corner of determined human behaviour where certain kinds of force and compulsion are absent.

Now, because this view asserts the compatibility of free will and determinism, it is usually called simply `compatibilism'. I think it is inadequate as a solution to the problem, and here is why. The problem about the freedom of the will is not about whether or not there are inner psychological reasons that cause us to do things as well as external physical causes and inner compulsions. Rather, it is about whether or not the causes of our behaviour, whatever they are, are sufficient to determine the behaviour so that things have to happen the way they do happen.

There's another way to put this problem. Is it ever true to say of a person that he could have done otherwise, all other conditions remaining the same? For example, given that a person chose to vote for the Tories, could he have chosen to vote for one of the other parties, all other conditions remaining the same? Now compatibilism doesn't really answer that question in a way that allows any scope for the ordinary notion of the freedom of the will. What it says is that all behaviour is determined in such a way that it couldn't have occurred otherwise, all other conditions remaining the same. Everything that happened was indeed determined. It's just that some things were determined by certain sorts of inner psychological causes (those which we call our 'reasons for acting') and not by external forces or psychological compulsions. So, we are still left with a problem. Is it ever true to say of a human being that he could have done otherwise?

The problem about compatibilism, then, is that it doesn't answer the question, 'Could we have done otherwise, all other conditions remaining the same?', in a way that is consistent with our belief in our own free will. Compatibilism, in short, denies the substance of free will while maintaining its verbal shell.

Let us try, then, to make a fresh start. I said that we have a conviction of our own free will simply based on the facts of human experience. But how reliable are those experiences? As I mentioned earlier, the typical case, often described by philosophers, which inclines us to believe in our own free will is a case where we confront a bunch of choices, reason about what is the best thing to do, make up our minds, and then do the thing we have decided to do.

But perhaps our belief that such experiences support the doctrine of human freedom is illusory. Consider this sort of example. A typical hypnosis experiment has the following form. Under hypnosis the patient is given a post-hypnotic suggestion. You can tell him, for example, to do some fairly trivial, harmless thing, such as, let's say, crawl around on the floor. After the patient comes out of hypnosis, he might be engaging in conversation, sitting, drinking coffee, when suddenly he says something like, 'What a fascinating floor in this room !', or 'I want to check out this rug', or 'I'm thinking of investing in floor coverings and I'd like to investigate this floor.' He then proceeds to crawl around on the floor. Now the interest of these cases is that the patient always gives some more or less adequate reason for doing what he does. That is, he seems to himself to be behaving freely. We, on the other hand, have good reasons to believe that his behaviour isn't free at all, that the reasons he gives for his apparent decision to crawl around on the floor are irrelevant, that his behaviour was determined in advance, that in fact he is in the grip of a post-hypnotic suggestion. Anybody who knew the facts about him could have predicted his behaviour in advance. Now, one way to pose the problem of determinism, or at least one aspect of the problem of determinism, is: 'Is all human behaviour like that?' Is all human behaviour like the man operating under a post-hypnotic suggestion?

But now if we take the example seriously, it looks as if it proves to be an argument for the freedom of the will and not against it. The agent thought he was acting freely, though in fact his behaviour was determined. But it seems empirically very unlikely that all human behaviour is like that. Sometimes people are suffering from the effects of hypnosis, and sometimes we know that they are in the grip of unconscious urges which they cannot control. But are they always like that? Is all behaviour determined by such psychological compulsions? If we try to treat psychological determinism as a factual claim about our behaviour, then it seems to be just plain false. The thesis of psychological determinism is that prior psychological causes determine all of our behaviour in the way that they determine the behaviour of the hypnosis subject or the heroin addict. On this view, all behaviour, in one way or another, is psychologically compulsive. But the available evidence suggests that such a thesis is false. We do indeed normally act on the basis of our intentional states — our beliefs, hopes, fears, desires, etc. — and in that sense our mental states function causally. But this form of cause and effect is not deterministic. We might have had exactly those mental states and still not have done what we did. As far as psychological causes are concerned, we could have done otherwise. Instances of hypnosis and psychologically compulsive behaviour on the other hand are usually pathological and easily distinguishable from normal free action. So, psychologically speaking, there is scope for human freedom.

But is this solution really an advance on compatibilism? Aren't we just saying, once again, that yes, all behaviour is determined, but what we call free behaviour is the sort determined by rational thought processes? Sometimes the conscious, rational thought processes don't make any difference, as in the hypnosis case, and sometimes they do, as in the normal case. Normal cases are those where we say the agent is really free. But of course those normal rational thought processes are as much determined as anything else.

Peter van Inwagen's Consequence Argument

So once again, don't we have the result that everything we do was entirely written in the book of history billions of years before we were born, and therefore, nothing we do is free in any philosophically interesting sense? If we choose to call our behaviour free, that is just a matter of adopting a traditional terminology. Just as we continue to speak of 'sunsets' even though we know the sun doesn't literally set; so we continue to speak of 'acting of our own free will' even though there is no such phenomenon.

One way to examine a philosophical thesis, or any other kind of a thesis for that matter, is to ask, 'What difference would it make? How would the world be any different if that thesis were true as opposed to how the world would be if that thesis were false?' Part of the appeal of determinism, I believe, is that it seems to be consistent with the way the world in fact proceeds, at least as far as we know anything about it from physics. That is, if determinism were true, then the world would proceed pretty much the way it does proceed, the only difference being that certain of our beliefs about its proceedings would be false. Those beliefs are important to us because they have to do with the belief that we could have done things differently from the way we did in fact do them. And this belief in turn connects with beliefs about moral responsibility and our own nature as persons. But if libertarianism, which is the thesis of free will, were true, it appears we would have to make some really radical changes in our beliefs about the world. In order for us to have radical freedom, it looks as if we would have to postulate that inside each of us was a self that was capable of interfering with the causal order of nature. That is, it looks as if we would have to contain some entity that was capable of making molecules swerve from their paths. I don't know if such a view is even intelligible, but it's certainly not consistent with what we know about how the world works from physics. And there is not the slightest evidence to suppose that we should abandon physical theory in favour of such a view.

So far, then, we seem to be getting exactly nowhere in our effort to resolve the conflict between determinism and the belief in the freedom of the will. Science allows no place for the freedom of the will, and indeterminism in physics offers no support for it. On the other hand, we are unable to give up the belief in the freedom of the will. Let us investigate both of these points a bit further.

Why exactly is there no room for the freedom of the will on the contemporary scientific view? Our basic explanatory mechanisms in physics work from the bottom up. That is to say, we explain the behaviour of surface features of a phenomenon such as the transparency of glass or the liquidity of water, in terms of the behaviour of microparticles such as molecules. And the relation of the mind to the brain is an example of such a relation. Mental features are caused by, and realised in neurophysiological phenomena, as I discussed in the first chapter. But we get causation from the mind to the body, that is we get top-down causation over a passage of time; and we get top-down causation over time because the top level and the bottom level go together. So, for example, suppose I wish to cause the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine at the axon end-plates of my motor neurons, I can do it by simply deciding to raise my arm and then raising it. Here, the mental event, the intention to raise my arm, causes the physical event, the release of acetylcholine — a case of top-down causation if ever there was one. But the top-down causation works only because the mental events are grounded in the neurophysiology to start with. So, corresponding to the description of the causal relations that go from the top to the bottom, there is another description of the same series of events where the causal relations bounce entirely along the bottom, that is, they are entirely a matter of neurons and neuron firings at synapses, etc. As long as we accept this conception of how nature works, then it doesn't seem that there is any scope for the freedom of the will because on this conception the mind can only affect nature in so far as it is a part of nature. But if so, then like the rest of nature, its features are determined at the basic micro-levels of physics.

This is an absolutely fundamental point in this chapter, so let me repeat it. The form of determinism that is ultimately worrisome is not psychological determinism. The idea that our states of mind are sufficient to determine everything we do is probably just false. The worrisome form of determinism is more basic and fundamental. Since all of the surface features of the world are entirely caused by and realised in systems of micro-elements, the behaviour of micro-elements is sufficient to determine everything that happens. Such a `bottom up' picture of the world allows for top-down causation (our minds, for example, can affect our bodies). But top-down causation only works because the top level is already caused by and realised in the bottom levels.

Well then, let's turn to the next obvious question. What is it about our experience that makes it impossible for us to abandon the belief in the freedom of the will? If freedom is an illusion, why is it an illusion we seem unable to abandon? The first thing to notice about our conception of human freedom is that it is essentially tied to consciousness. We only attribute freedom to conscious beings. If, for example, somebody built a robot which we believed to be totally unconscious, we would never feel any inclination to call it free. Even if we found its behaviour random and unpredictable, we would not say that it was acting freely in the sense that we think of ourselves as acting freely. If on the other hand somebody built a robot that we became convinced had consciousness, in the same sense that we do, then it would at least be an open question whether or not that robot had freedom of the will.

The second point to note is that it is not just any state of the consciousness that gives us the conviction of human freedom. If life consisted entirely of the reception of passive perceptions, then it seems to me we would never so much as form the idea of human freedom. If you imagine yourself totally immobile, totally unable to move, and unable even to determine the course of your own thoughts, but still receiving stimuli, for example, periodic mildly painful sensations, there would not be the slightest inclination to conclude that you have freedom of the will.

I said earlier that most philosophers think that the conviction of human freedom is somehow essentially tied to the process of rational decision-making. But I think that is only partially true. In fact, weighing up reasons is only a very special case of the experience that gives us the conviction of freedom. The characteristic experience that gives us the conviction of human freedom, and it is an experience from which we are unable to strip away the conviction of freedom, is the experience of engaging in voluntary, intentional human actions. In our discussion of intentionality we concentrated on that form of intentionality which consisted in conscious intentions in action, intentionality which is causal in the way that I described, and whose conditions of satisfaction are that certain bodily movements occur, and that they occur as caused by that very intention in action. It is this experience which is the foundation stone of our belief in the freedom of the will. Why? Reflect very carefully on the character of the experiences you have as you engage in normal, everyday ordinary human actions. You will sense the possibility of alternative courses of action built into these experiences. Raise your arm or walk across the room or take a drink of water, and you will see that at any point in the experience you have a sense of alternative courses of action open to you.

If one tried to express it in words, the difference between the experience of perceiving and the experience of acting is that in perceiving one has the sense: 'This is happening to me,' and in acting one has the sense: 'I am making this happen.' But the sense that 'I am making this happen' carries with it the sense that 'I could be doing something else'. In normal behaviour, each thing we do carries the conviction, valid or invalid, that we could be doing something else right here and now, that is, all other conditions remaining the same. This, I submit, is the source of our unshakable conviction of our own free will. It is perhaps important to emphasise that I am discussing normal human action. If one is in the grip of a great passion, if one is in a great rage, for example, one loses this sense of freedom and one can even be surprised to discover what one is doing.

Once we notice this feature of the experience of acting, a great many of the puzzling phenomena I mentioned earlier are easily explained. Why for example do we feel that the man in the case of post-hypnotic suggestion is not acting freely in the sense in which we are, even though he might think that he is acting freely? The reason is that in an important sense he doesn't know what he is doing. His actual intention-in-action is totally unconscious. The options that he sees as available to him are irrelevant to the actual motivation of his action. Notice also that the compatibilist examples of 'forced' behaviour still, in many cases, involve the experience of freedom. If somebody tells me to do something at gunpoint, even in such a case I have an experience which has the sense of alternative courses of action built into it. If, for example, I am instructed to walk across the room at gunpoint, still part of the experience is that I sense that it is literally open to me at any step to do something else. The experience of freedom is thus an essential component of any case of acting with an intention.

Again, you can see this if you contrast the normal case of action with the Penfield cases, where stimulation of the motor cortex produces an involuntary movement of the arm or leg. In such a case the patient experiences the movement passively, as he would experience a sound or a sensation of pain. Unlike intentional actions, there are no options built into the experience. To see this point clearly, try to imagine that a portion of your life was like the Penfield experiments on a grand scale. Instead of walking across the room you simply find that your body is moving across the room; instead of speaking you simply hear and feel words coming out of your mouth. Imagine your experiences are those of a purely passive but conscious puppet and you will have imagined away the experience of freedom. But in the typical case of intentional action, there is no way we can carve off the experience of freedom. It is an essential part of the experience of acting.

This also explains, I believe, why we cannot give up our conviction of freedom. We find it easy to give up the conviction that the earth is flat as soon as we understand the evidence for the heliocentric theory of the solar system. Similarly when we look at a sunset, in spite of appearances we do not feel compelled to believe that the sun is setting behind the earth, we believe that the appearance of the sun setting is simply an illusion created by the rotation of the earth. In each case it is possible to give up a commonsense conviction because the hypothesis that replaces it both accounts for the experiences that led to that conviction in the first place as well as explaining a whole lot of other facts that the commonsense view is unable to account for. That is why we gave up the belief in a flat earth and literal 'sunsets' in favour of the Copernican conception of the solar system. But we can't similarly give up the conviction of freedom because that conviction is built into every normal, conscious intentional action. And we use this conviction in identifying and explaining actions. This sense of freedom is not just a feature of deliberation, but is part of any action, whether premeditated or spontaneous. The point has nothing essentially to do with deliberation; deliberation is simply a special case.

We don't navigate the earth on the assumption of a flat earth, even though the earth looks flat, but we do act on the assumption of freedom. In fact we can't act otherwise than on the assumption of freedom, no matter how much we learn about how the world works as a determined physical system.

We can now draw the conclusions that are implicit in this discussion. First, if the worry about determinism is a worry that all of our behaviour is in fact psychologically compulsive, then it appears that the worry is unwarranted. Insofar as psychological determinism is an empirical hypothesis like any other, then the evidence we presently have available to us suggests it is false. Thus, this does give us a modified form of compatibilism. It gives us the view that psychological libertarianism is compatible with physical determinism.

Secondly, it even gives us a sense of 'could have' in which people's behaviour, though determined, is such that in that sense they could have done otherwise: The sense is simply that as far as the psychological factors were concerned, they could have done otherwise. The notions of ability, of what we are able to do and what we could have done, are often relative to some such set of criteria. For example, I could have voted for Carter in the 1980 American election, even if I did not; but I could not have voted for George Washington. He was not a candidate. So there is a sense of 'could have', in which there were a range of choices available to me, and in that sense there were a lot of things I could have done, all other things being equal, which I did not do. Similarly, because the psychological factors operating on me do not always, or even in general, compel me to behave in a particular fashion, I often, psychologically speaking, could have done something different from what I did in fact do.

But third, this form of compatibilism still does not give us anything like the resolution of the conflict between freedom and determinism that our urge to radical libertarianism really demands. As long as we accept the bottom-up conception of physical explanation, and it is a conception on which the past three hundred years of science are based, then psychological facts about ourselves, like any other higher level facts, are entirely causally explicable in terms of and entirely realised in systems of elements at the fundamental micro-physical level. Our conception of physical reality simply does not allow for radical freedom.

Fourth, and finally, for reasons I don't really understand, evolution has given us a form of experience of voluntary action where the experience of freedom, that is to say, the experience of the sense of alternative possibilities, is built into the very structure of conscious, voluntary, intentional human behaviour. For that reason, I believe, neither this discussion nor any other will ever convince us that our behaviour is unfree.

My aim in this book has been to try to characterise the relationships between the conception that we have of ourselves as rational, free, conscious, mindful agents with a conception that we have of the world as consisting of mindless, meaningless, physical particles. It is tempting to think that just as we have discovered that large portions of common sense do not adequately represent how the world really works, so we might discover that our conception of ourselves and our behaviour is entirely false. But there are limits on this possibility. The distinction between reality and appearance cannot apply to the very existence of consciousness. For if it seems to me that I'm conscious, I am conscious. We could discover all kinds of startling things about ourselves and our behaviour; but we cannot discover that we do not have minds, that they do not contain conscious, subjective, intentionalistic mental states; nor could we discover that we do not at least try to engage in voluntary, free, intentional actions. The problem I have set myself is not to prove the existence of these things, but to examine their status and their implications for our conceptions of the rest of nature. My general theme has been that, with certain important exceptions, our commonsense mentalistic conception of ourselves is perfectly consistent with our conception of nature as a physical system.

Bibliography

John Searle, Freedom and Neurobiology (New York, Columbia U. Press, 2007)

|